For thousands of years Indigenous peoples on this continent subsisted by harvesting food from abundant, natural ecosystems which maintained balance in the environment. Regenerative principles were inherent in Indigenous land stewardship. Thought was given to harvest sustainably, so that abundance was maintained for generations into the future and ecosystems so essential to fertility and the maintenance of climate and water cycles were not disturbed. The industrial food system has had a more shortsighted and extractive approach and we find ourselves now in a position of trying to restore the damage that was done in the face of massive biodiversity loss and climate change. We are now recognizing that ecosystem services are crucial to the survival of human civilization. Preserving forests and wild spaces, wetlands and grasslands is critical to maintaining a liveable climate and keeping temperature increases below 1.5 degrees according to scientists.

With the recognition of the urgency of restoring a baseline of natural ecosystems to restore climate, Indigenous activists are finding more allies in their fight to protect the ecosystems which provide the basis for their traditional food and lifestyles. In this article I will touch on two initiatives championed by people from Indigenous communities. One is the restoration of prairie savannah with buffalo and the other is wetland restoration with wild rice.

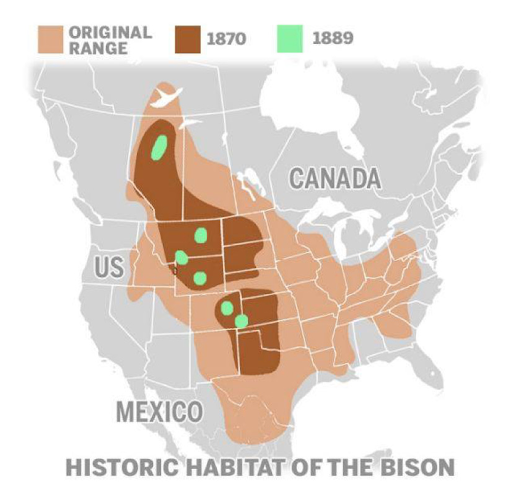

Once, much of the central area of Turtle Island (North America) was roamed by enormous herds of bison. The buffalo was a keystone species, allowing the grasslands and native prairie plants to flourish. It was the largest carbon sink in North America. The Lakota people had a lifestyle that was intimately connected to the migration of the buffalo; the animal was central to their lives. Buffalo meat is a superfood rich in protein, iron and omega-3 fatty acids.

Today, there is an emerging awareness that this richness which has been virtually obliterated, is actually of great value not only to Indigenous communities, but to all of us in our fight against climate change. A handful of initiatives have been growing with the aim of returning buffalo to the prairies and re-establishing the grassland ecosystem. One of these is The Tanka Fund. This is an organization with the mission of helping Indigenous ranchers on reservation land to establish buffalo herds and to make a living from it. Tanka means “great” or “large” in the sense of the interconnectedness of all life, in the Lakota language. Through the project, the Tanka team envisions a return of greatness to the land, to the people and to the economy.

To the Anishinaabe people, Manoomin, or wild rice was as central to their lifestyle as the buffalo were to the Lakota. Wild rice grows in the shallow edges of lakes. Coastal wetlands, like grasslands, have a huge ecological importance which has been long overlooked. Wetlands are the kidneys of the earth. They purify toxins from the water. They protect the coasts from storm surges and winds and give flood waters a place to go. They are home to more than a third of endangered species. Wetlands can store vast quantities of organic matter for hundreds of years, therefore providing a carbon sink equal to or superior to forest land.

Wild rice, not actually related to rice, is an indigenous plant to North America and has been growing around the Great Lakes and boreal forest regions for thousands of years. It had largely been wiped out due to water pollution, to development, to tampering with water levels (wild rice requires shallow water) and to removal by people who didn’t understand its value and thought of it as a weed. Today, there are projects to bring it back in a number of places in Canada and the US.

James Whetung, Founder of Black Duck Wild Rice has been on a mission for the past 38 years to restore the sacred plant to Rice Lake, home to the Curve Lake First Nation. Some seed of manoomin had been carried from Rice Lake down to the Mississippi River several generations back. In 1982, James Whetung attended a food security gathering in Ardock by the Mississippi and returned with manoomin seed and a passion to restore the good seed to his native lands. He seeds and harvests the manoomin, but he is also determined to educate people on the value not only of the precious food but the culture and traditions around it. He hosts the Manoomin camp in the summer and in the fall, where people of all backgrounds come together to learn about the history of wild rice and how to gather, roast, dance and winnow it.

If you want to know more, here is a short video about James and his mission: Black Duck wild rice. James will also be joining us for a webinar about his work on November 12th and you are welcome to register for it.

The value of restoring these native food systems is very much in alignment with regenerative land management. By sustainably stewarding the land which produces these valuable and nutritious foods, we are in line with the vision of scientists who tell us that a healthy planet depends on restoring a third of the world’s wild ecosystems. With enough of these ecosystems functioning we can restore our air, water, soil and biodiversity.