All over Canada, whether shorter or longer, winter is a time of rest from the garden or the farm. We get some snow. It is too cold for plants to grow. But what is happening under the ground? Has everything stopped? Not entirely, but it does slow down!

Most microorganisms that associate with plant roots have optimal functioning in a temperature range from 25-30°C. As the temperature gets closer to freezing, the number of microorganisms which are active and the rate of their activity will slow down. But there are usually some other microorganisms which are adapted to the new conditions. So while the primary organisms – which are active in the summer when plants are growing – may stop functioning in the winter, there are others who will increase their rate of activity in the microbial communities as conditions change. For instance, many fungal decomposers have a lower optimal temperature range than bacteria. So while the fungi might not function at full capacity through the winter, in the spring and fall, as temperatures transition, their activity in the soil may be more present. This is why spring and fall are the best seasons to spot mushrooms, which are the fruiting bodies of the fungi.

How far down the soil actually freezes, stopping microbial activity, depends on many factors. It can be anywhere from a few inches at the surface to a meter deep. Nevertheless, underneath the frozen layer, life is still present. Creatures such as toads and earthworms produce their own antifreeze and burrow down deep to survive the cold. Others lay eggs or make spores to wake up again and restart life when the conditions are favorable.

Both organic matter and snow cover provide insulation for your soils. It is advantageous to keep your soil covered with winter cover crops or plant debris because it helps to shelter the microbial life from a deep freeze. It is also a good idea to provide windbreaks to keep your snow cover from blowing away. In addition, snowmelt will sink into your soil in the spring and if your soil percolates well from good regenerative management, you will be storing water in reserve to help make it through the dry, hot summer months.

Tips from Ananda’s garden

In the fall I plant cover crops after I harvest garlic, potatoes, tomatoes and frost sensitive crops which get harvested earlier. This year I used a mixture of oats, forage peas and mustard. These will be killed off by the cold, leaving plant debris in the spring. In some areas where the crops were harvested later, I sowed winter rye, which will start to grow again in the spring, requiring me to smother it with an occultation tarp (a heavy black plastic sheet that kills the plants by shutting out the light), or turn it in before I can plant.

My garden is about an acre, spread out in a few different sections. It is small enough that I can use mulches of leaves and straw to cover the ground. I collect the bags of leaves that people in a nearby town pick up from their lawns and use them to make compost and to cover parts of my garden. After planting my garlic, I cover the beds with leaves and top it with some rotted straw to keep the leaves from blowing away. In the spring this mulch will keep the weeds from starting and it will be full of worms, onsite vermicompost! I also put mulch on beds where I have parsnips and leeks which will be harvested in the spring and on perennial flower beds. I use a thick mulch of wood chips around the roots of my berry bushes.

Tips from Alix’s farm

Our small-scale vegetable and cut-flower farm, Larkspur Farm, is located in Western Quebec in zone 4A. We grow and market our food and flowers until the end of October. When we are planning for the end of the season, two key questions guide the actions we choose to take around soil health. How can we feed the soil food web for as long as possible? If we don’t have plants growing, how can we keep the soil covered during the winter? As a working farm, the strategies we use change from year to year. The decisions we make are dependent on timing, labor capacity, weather, and crop rotation.

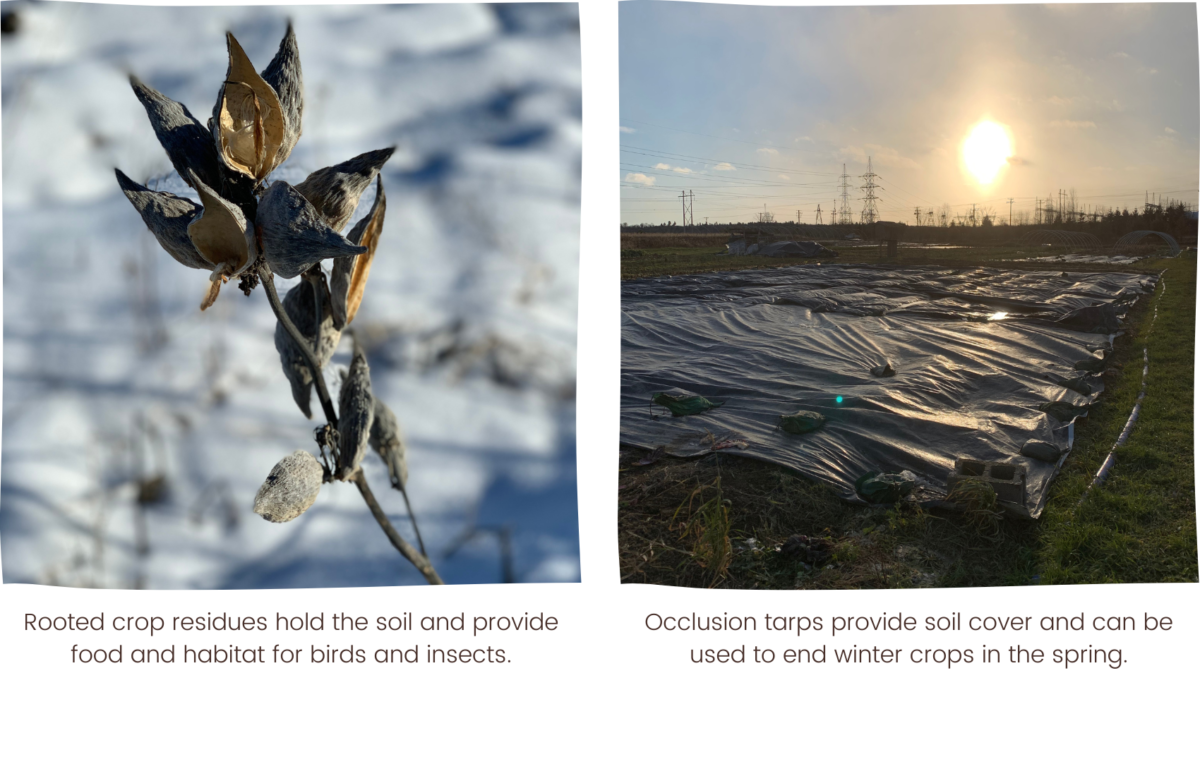

One of the easiest actions we take is to leave crop residues in place and not prepare beds until the spring. For example, we actually leave our annual flower field intact until the spring. These plants have been photosynthesizing for months and have grown thick, tall stalks and abundant roots. Not only will these plants feed the soil microbial ecosystem until frost, but the roots will hold the soil over the winter and provide food and habitat for birds and insects.

When the timing works out, we will also use winter-kill cover crops such as oats and peas and annual clover. These crops will establish in the fall even with some light frosts continuing to provide nourishment for the soil. We also use a combination of mulches on our permanent beds including crop residues (e.g. storage carrot tops), compost, straw, and black tarps.

Tips from Sara’s urban collective garden

On sème‘s collective educational gardens are in the heart of the city. We like to create partnerships to bring resources from local activity back to the garden. For example, we cover our walkways and food forests with ramial chipped wood from tree trimmings donated by local neighborhood pruners. This year, we were fortunate to work with a company that provides organic Halloween decorations and reclaims them to give back to local initiatives. We were able to cover several of our garden beds with organic straw and corn stalks. Our friends at Polliflora have also taught us to leave some plants rooted, such as sunflowers, so that the stems can provide shelter for pollinators and other insects during the winter. We love our willow windbreak, which helps mitigate wind gusts and provides a place for water retention in the garden. Finally, our friends at Regeneration Canada have taught us that roots help to hold the soil in place, thus limiting erosion, and provide food for soil life.

Tips from Meagan’s farm

Because Patch Farm is pasture-based livestock farm, and our cattle live outside year-round, it is extremely important that we plan our moves very carefully – especially in the spring and fall. The transition from fall to winter is a time of high rainfall here in southern Quebec, so we start bringing the cattle closer to home by early November and keep them on a “sacrifice paddock” where we feed them hay. This ensures that there’s minimal compaction and pugging, which is usually the result of leaving the animals out on very soggy ground. While having very dense communities of deep-rooted grasses can go a long way to help reduce this kind of damage, it is not always easy to achieve, depending on the ecological conditions on your farm. Our farm is nestled in a little valley and happens to have a lot of low-lying lands that don’t drain very well and that are subject to occasional flooding in spring and fall. So we have to be very careful to keep all traffic – animal and machine – to a minimum during this transition period.

So what do we do to protect the soil through the winter? First, we make sure we leave a good amount of residue in our pastures. I like to leave at least 6” of grass behind. This helps insulate the plants and roots under snow cover, creates habitat for small critters, and gives the pastures a leg-up in the spring because there are more leaves for capturing sunlight. And if I plan things right, I can even leave behind 12”-16” of grass that the cattle can graze during the winter. It doesn’t supply 100% of their forage needs, but every little bit helps. We also like to bale graze as much as possible over the winter. We feed hay in the sacrifice paddock until the ground is frozen and then we put hay directly out on the fields. This is much better for the cattle as they stay cleaner and drier. It’s also better for the soil because we are leaving behind organic matter in the form of manure, urine and hay residue. It’s also a lot cheaper and more efficient to put hay bales out rather than to scoop up manure in the spring and spread it on the fields.

So, using whatever methods are appropriate for the context where you grow, tuck your soil in with plenty of organic matter to eat and a nice layer of cover. You can take a break in the winter and some of your soil microbes will too, but some will be getting ready for spring!