What we learned at the 2021 Living Soils Symposium

Last month, we held the 4th edition of our Living Soils Symposium, the second one to be held online. With over 500 participants from over 25 countries, we were thrilled to see the active engagement from the community around soil regeneration, despite the high number of online events this past year. This was the first time we focused the event on a specific theme: Hydrating Landscapes to Mitigate Climate Change.

While we planned for the conversations at the Symposium to be oriented around the theme of water and soil regeneration, we hoped to deepen our common understanding of regenerative agriculture as it intersects with equity, justice and decolonization. We were amazed at the prevailing emphasis on the need to understand the lasting legacy of colonialism as an underlying cause of our current climate crisis, and of decolonization as a way to chart a path forward. Fighting for racial justice goes hand in hand with healing our food system and soils.

The opening sessions set the tone for the week. Honouring Water, Healing our World, introduced us to two Indigenous women, Mary Anne Caibaiosai and Dawn Morrison, both of whom are Water Walkers. Water walking is an Indigenous tradition both to heal water and create relationship with the water. According to Mary Anne, “in many ways a water walk is a spiritual activity. You become changed and you start understanding what water is, and what it means. When you wake up at 3 or 4 in the morning, you hear all of creation waking up, you start understanding that relationship.” They spoke about how with an Indigenous worldview, water and all of nature is alive and is our relative. “We are the land. We can’t be separated from it,” said Dawn. Water is the source of all life. When we treat it as a resource to be extracted for our use, we are operating with a colonial mindset – putting ourselves and our needs above everything else and feeling entitled to exploit the nature around us.

Next, Didi Persehouse and Walter Jehne set the table to explain the soil-water-climate connection. In the regenerative movement, the prevailing narrative is that we can mitigate the climate crisis through the carbon cycle, i.e. by drawing down carbon into soils. However, according to Australian soil microbiologist and climate scientist Water Jehne, atmospheric carbon is more of a symptom than a cause. The effects of climate change are the result of a dysfunctional water cycle. Droughts, floods, wildfires and violent storms are caused by disruptions to the small water cycle. Water flowing from the clouds to the land and back to the sea is the large water cycle. Water circulates over a great distance and ultimately returns to the sea. The small water cycle refers to the movement of water in a bioregion between earth and the atmosphere, which is mediated by plants and soil.

When soil is healthy and covered by green plants, water infiltrates the earth, refills the aquifers and stores water for long enough to give resilience in drier periods. As Didi put it, ”plants serve as billions of tiny dams across the entire landscape.” Plant transpiration cools the temperature and even increases the frequency of rainfall. By depleting and compacting our soils, and by removing most of the earth’s forest cover, we are on the road to desertifying large swaths of our planet, while contributing to more extreme weather events, and a global water scarcity crisis.

Building up the soil carbon sponge and preserving wet areas on the land are how, through regenerative land stewardship, we can restore the small water cycle, while providing resilience to climate extremes. The sessions that followed went into more detail on how to do that.

We learned from ecologist Glynnis Hood how beavers contribute to hydrology through their natural inclination to build dams and trap water which slowly percolates into the landscape. Alberta farmer Takota Coen described how humans can imitate beavers and explained how he brought back water flow on his family farm. He created dams and collected and stored every drop of water on his land to the extent that even his neighbours’ well started to function again!

Odette Ménard and Merrin Macrae talked about how too much or too little water are two sides of the same coin and how we can combat soil compaction and build soil carbon with good management practices instead of resorting right away to drainage and irrigation. Odette stressed the need to “cover and feed the soil at all times.” Well-managed herds of grazing ruminants can restore the hydrological function in arid grassland areas as we heard from the experience of Precious Phiri in Zimbabwe and Jon Griggs in Nevada. Both saw fertility, water, and habitats restored through their projects with grazing. Root systems of well-managed perennial grasslands help the water and the carbon infiltrate deeper into the landscape.

Wetlands and peat bogs are important from a carbon storage perspective, but also as water sinks to keep the land hydrated. We learned from Line Rochefort that these can be and are being restored. The industry standard for the peat industry in North America is now to systematically restore the peat bogs they harvest from. ALUS Canada provides land owners with funding and technical assistance to restore wetlands on their properties. Where wetlands were once seen as unproductive land and filled in to grow crops, we are now waking up to the fact that they are critical in keeping the small water cycle functioning.

Another session dealt with protecting our drinking water and keeping our organic soils from being washed away by erosion. We learned about inoculating soil with perennial plant biomass and about allowing the space for rivers to meander so they won’t carry all their sediment away. Simon Côté of Arbre-Évolution told us how their project, Carbone Riverain, intends to compensate Quebec farmers to protect and expand riparian buffers on their farms through carbon credits.

We pivoted to focusing on cities and heard about some progressive initiatives happening in Montreal and Vancouver in waste management green infrastructure. Research conducted by Michel Labrecque of the Université de Montréal demonstrated that leachate from landfill sites can be bioremediated with plants. Willow is a particularly powerful tool for detoxifying contaminated sites. Next, Sheri Deboer and Julie McManus of the City of Vancouver shared the innovative projects being implemented by the city to manage rainwater by sinking it into the ground with plants instead of only carrying it away with sewer pipes.

In the Cultivating Racial Equity in Regenerative Agriculture session, three BIPOC womxn, Leticia Deawuo of Black Creek Community Farm, Dawn Morrison of the Working Group on Indigenous Food Sovereignty and Michaela Cruz of Healing Hands Farm had a stirring conversation facilitated by Angel Beyde of Ecological Farmers Association of Ontario and Good Fortune Farmstead. The presenters touched on the historical context of colonialism on Turtle Island. Dawn explained that the lands stewarded by Indigenous people were stolen and given to settler farmers.

In addition, agriculture in North America and other colonial states was built on the backs of Black slaves. Leticia reminded us that “the system is not broken – it is working the way it was designed to work, on the backs of oppressed peoples.” Today, a large portion of Canadian agriculture depends on poorly paid and precariously employed migrant workers. Michaela discussed the difficulty that people of colour experience in accessing and owning land. Dawn stressed, “our existence as Indigenous peoples is a conservationist method and we need all humans to see themselves as a part of nature. That’s the key to maintaining biological diversity.” Indeed, even though Indigenous Peoples make up 5% of the global population, the remaining lands they steward hold 80% of the world’s biodiversity.

If we are going to turn this ecological crisis around, we have to dismantle racism. Regenerative land stewardship must be based on a regenerative mindset and not the colonial mindset of exploiting resources for the benefit of a few corporations. You can watch the full session here.

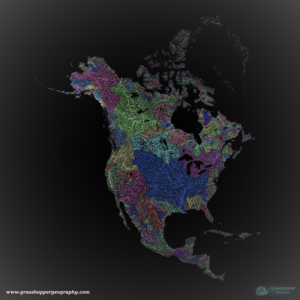

The final sessions tied together the themes of water and equity. In Landscape Level Change we looked at how we can work together to maintain functional ecosystems. Water knows no boundaries, as this map of the watersheds from Grasshopper geography shows us.

Watersheds span different jurisdictions and if we are to have desirable impacts over a landscape we need to work across political jurisdictions. Indigenous scholar Michael Blackstock framed the conversation using the concept of Blue Ecology, an attitude which interweaves the strength of Indigenous ways of knowing with western science, centring the idea that water is alive and fundamental to life. He emphasized that it is not a competition between ways of knowing. We then heard about two inspiring multi-stakeholder projects. Kim Stephens told us about the Partnership for Water Sustainability in BC which brings together municipal governments and land stewardship groups to implement projects for watershed health, rainwater management and green infrastructure. Finally we heard from Kimberly Cornish of Food Water Wellness about her efforts to bring together stakeholders on the Prairies to validate the benefits of regenerative agriculture on soil carbon sequestration.

In the final session Zach Weiss spoke about decolonizing water and revisited many of the concepts that were outlined in the first sessions. The disruptions to the small water cycle caused by our exploitative management of earth’s resources are causing a serious risk to food security all around the world. Our mismanagement of land to extract resources is resulting in the degradation of now over ⅓ of the world’s land surface. He advocated for a grassroots movement based on community-driven decentralized water retention to create a New Water Paradigm based on love and respect for nature and water. As he put it, “there’s no peace without water.” View his presentation here.

Throughout the week, small breakout groups after each session enabled participants to meet each other, share thoughts and network. These connections really helped to lift the virtual event to a different level and brought us some of the energy we would normally get at a live event. There was even a social hour with games and live music by singer-songwriter Bet Smith accompanied by Rob Currie.

After the final conference, participants were led by facilitator Leah Vineberg in a reflection of how we can each take actions in our own lives to build on the insights we gathered from the week.

We hope that the experience of the Living Soils Symposium will once again inspire participants to make changes in their own lives and collaborate with others to accelerate the grassroots regenerative movement so needed around the world. We are reflecting deeply on the perspectives we heard and thinking about approaches to decolonizing water and to understanding how it moves through the planet. As Precious Phiri said, “we are students of this land that we work with.”

The recordings of the Symposium are available for free for Regeneration Canada members and upon a donation for non-members in our Media Library.